Malware Just Got Its Free Passes Back!

TL;DR

As detection strategies increasingly emphasize call stack telemetry and validation, adversaries are adapting with more sophisticated evasion techniques. Building on our prior work with Stack Moonwalk and the Eclipse detection algorithm, this research introduces a new “way” of leveraging moonwalking that extend beyond basic desynchronization.

In this article, we’ll present a PoC to extend FullMoon, which will allow us not only to spoof the call stack to our call, hiding the real origin of the call during the program execution, but also avoid several indicators and traces usually left with the adoption of Moonwalking. Finally, we’ll show out it is possible to refine the technique not only to spoof the stack at every call, but also encrypt our malware while executing virtually any target Windows API.

Overview

The research covered in this article is a follow-up to the joint research of Arash Parsa, aka waldo-irc, Athanasios Tserpelis, aka trickster0, and me (Alessandro Magnosi, aka klezVirus), presented in DEFCON 31 titled “StackMoonwalk”.

A blog post regarding this technique can be found in this very blog. I would recommend giving it a read as it will be useful to better understand the content of this post.

In 2023, I shared a brief teaser of what I’m about to explore here. It may have sparked curiosity, but offered little detail, leaving many wondering what the goal really was and how it actually worked.

Introduction

As previously described, the Stack Moonwalk technique requires a very specific set of stack frames to spoof the call stack while keeping it fully unwindable.

Although Windows provides many such frames (e.g., over 100 just in KernelBase), finding a sequence that is both unwindable and logically valid for the OS is non-trivial.

Frame Sequence Definition

Let:

Qbe a functionQ(s) = Fdenote the frame allocated by functionQon the stack- A sequence of frames be represented as:

F₁, F₂, ..., Fₙfor some integern

Define:

C[i]as the set of instructions belonging to functionFᵢ- A specific instruction as

Cᵢⱼ(thejᵗʰinstruction of functionFᵢ)

Valid Stack Frame Sequence Requirements

For a valid and logically sound sequence of frames F[1-4], the following conditions must hold:

F₁performs aUWOP_SET_FPREGoperation.F₂performs aUWOP_PUSH_NONVOLoperation onRBP.F₃contains a ROP gadget:C₃g = JMP [NON_VOL_REG]

F₄only performs aUWOP_ALLOC_SMALL, and ends with a stack pivot gadget:C₄g = ADD RSP, X; RET- Where

Xis large enough to store all parameters of the spoofed function.

- For

Fᵢwherei ∈ [1, 2], there exists a call instructionCᵢⱼsuch that:Cᵢ = CALL Fᵢ₊₁

- For

Fᵢwherei ∈ [3, 4], there exists:Cᵢ = CALL Fᵢ₊₁, andCᵢ₊₁ == Cᵢg(gadget instruction follows the call)

Detection

To detect misuse of the Stack Moonwalk technique, we presented the Eclipse Algorithm, which extends RtlVirtualUnwind with strict checks on instructions preceding the return address.

For each frame in reverse order, the following checks are applied:

- Is the instruction at the return address a JOP / COP / ROP gadget?

- Is the instruction preceding the return address a

CALL? - Does the address of the

CALLmatch the Begin-Address of the current frame?

How Eclipse was adapted by major EDRs

Building on ideas similar to Eclipse, Elastic Security Labs has taken significant steps to operationalize call stack inspection within real-world detection pipelines. Their approach enhances traditional stack unwinding by correlating runtime stack traces with rich symbol and module metadata, aiming to detect anomalous or indirect execution paths, with particular focus on those used to proxy sensitive API calls.

Elastic’s detection logic targets the same evasion surfaces Eclipse highlighted, but with greater environmental context and process-level telemetry, identifying patterns such as trampoline chains, callback-based execution, or stack desynchronization.

Before evaluating evasions, it is essential to clarify what constitutes a detection in call stack analysis. We baselined our research on Elastic’s operational model. A detection event is not a single anomaly, but the result of stack inspection augmented by semantic labeling. This detection logic distinguishes several categories of suspicious conditions within a call stack, summarized as follows:

| Label | Description |

|---|---|

| native_api | A direct call to the Native API, bypassing the Win32 API layer |

| direct_syscall | A syscall originating from outside the standard API layers |

| proxy_call | The stack indicates a proxied call meant to mask the real origin |

| shellcode | Executable memory outside image mappings invokes a sensitive API |

| image_indirect_call | A call preceded by a dynamic function resolution |

| image_rop | Stack entry reached without a proper CALL instruction (ROP behavior) |

| image_rwx | The return address in the stack points to a RWX image |

| unbacked_rwx | Stack references non-image, writable memory. Common in JIT or shellcode |

| truncated_stack | The stack ends prematurely, suggesting tampering or corruption |

Detecting Moonwalking

In the article Call Stacks: No More Free Passes For Malware, John Uhlmann details recent improvements to Elastic’s call stack enrichment capabilities designed to detect common and evasive call stack anomalies. The content offers valuable insight for defenders seeking to enhance their understanding of call stack telemetry and its role in modern detection strategies.

Props to Elastic for publishing detailed blogs and detection rules. This kind of transparency not only strengthens defensive capabilities but also sparks meaningful community contributions that drive both offensive and defensive research forward.

These labels illustrate that detection relies on a two-phases model:

- Caller Identification: The system must reliably unwind the call stack and locate the frame responsible for invoking a sensitive API (e.g., VirtualAllocEx, NtCreateThreadEx, etc.).

- Caller Qualification: Once identified, the system assesses whether the caller frame exhibits known red flags—such as unwritable code memory, improper call instruction origins, or unbacked executable memory regions.

In practice, this means that stack-based detection logic is heavily dependent on the accuracy of stack resolution and the trustworthiness of metadata (e.g., unwind info, PE mappings, and memory permissions). This creates an inherent limitation: the source of truth for detection is ultimately the call stack itself, which can be manipulated by adversaries to hide execution provenance and evade categorization under any of the above labels.

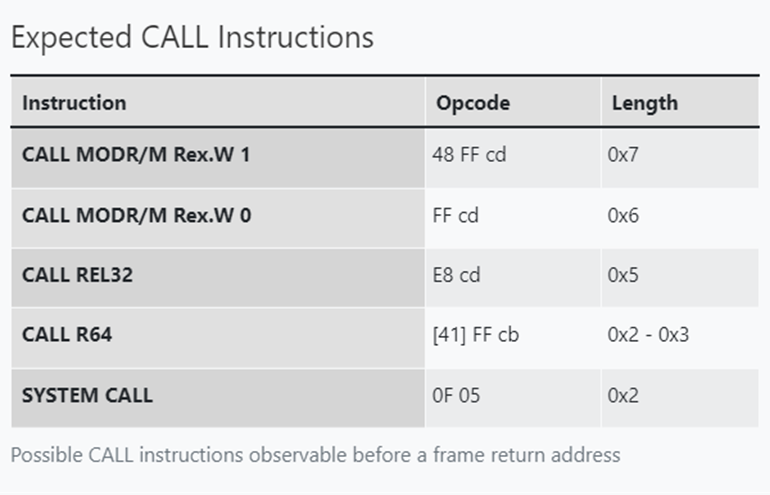

A clear example of that is immediately observed in the specific detection logic provided by Elastic, which was in fact derived from our initial implementation of the Eclipse algorithm: detecting a spoofed frame by checking if the instruction before the return (i.e., the call site) is indeed a call instruction. This means that, going back in the stack, we ensure that the instruction is among the ones listed below.

Another example is the reliance on detecting specific concealment or desynchronization (desync) gadgets in the call stack. The problem with detecting conceal-frames is that a vast number of legitimate frame functions in kernel32 and kernelbase exhibit similar structural patterns, making reliable differentiation difficult. Similarly, the reliance on identifying specific desync gadgets is flawed: numerous viable alternatives exist for invoking the restore function that do not depend on fixed registers or instruction sequences.

Elastic’s detection logic also assumes that by concealing the original caller module in memory, the resulting user module will be “undetermined”. While this holds in certain implementations of the technique, we will demonstrate why this assumption fails under broader conditions.

In scenarios where the caller can be identified, it becomes possible to further analyze the associated memory region for anomalies, which could lead to more precise detection. In the case of stack moonwalking, it is generally assumed that the module does not remain encrypted in memory due to its inherently dynamic behavior (ROP based, to be precise). In other words, it is assumed that the caller cannot encrypt itself while executing. However, as we will show, even this assumption is fundamentally incorrect.

Let the fun begin! Getting back our free passes!

Bypassing Call Instruction Checks

The main issue with this kind of detection logic is that, unfortunately, several gadgets exist in Windows that can be used as suitable desync gadgets and are also prepended by a spurious call instruction.

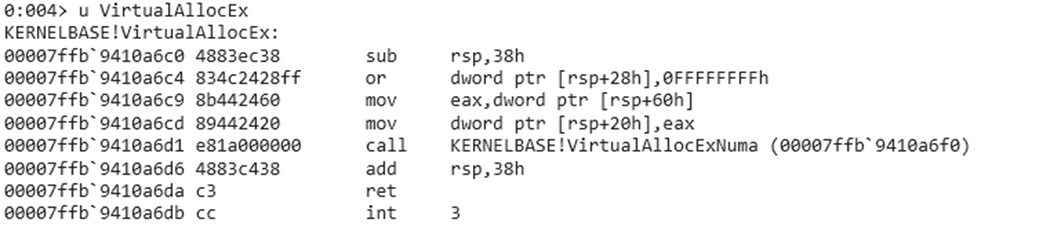

For conceal gadgets, many functions are indeed “wrappers” that are responsible only for the initialization of certain parameters, then literally returns the wrapped function. An example is VirtualAllocEx, which in turns calls VirtualAllocExNuma:

As observed, this function qualifies as a valid conceal gadget and includes legitimate call instruction at the expected call site.

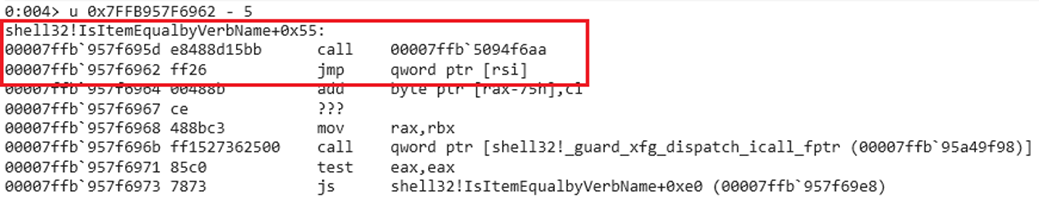

The case for desync gadgets is more nuanced. On Windows, there are multiple opportunities to locate desync gadgets that appear to contain a valid call instruction. While the specified target address may sometimes point to an unallocated memory page, it is not unrealistic for it to point to a valid region in memory. Therefore, it is essential not only to verify that the instruction is indeed a call, but also to confirm that the destination address is both resolvable and maps to a feasible memory location.

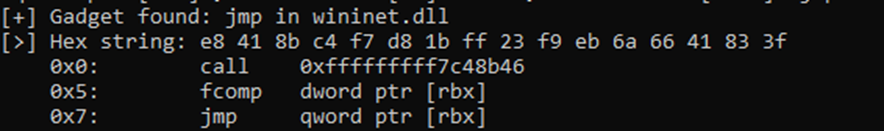

We go a step further by identifying gadgets capable of bypassing Eclipse’s JMP/ROP/COP detection logic. While more complex, the core bypass strategy remains the same: locating execution paths through carefully selected, compliant gadgets.

Interestingly, we can also abuse lesser-known gadgets as “padding” between the call and the desync gadget, provided they are innocuous in terms of stack or return value modification. Instructions like fcomp, for example, introduce no meaningful side effects and can be used to obfuscate the control flow without disrupting execution.

Bypassing “Undetermined” Final User Module and/or Private RW/X Memory Regions

Another easily bypassed detection technique is the assumption that the final caller module must remain unresolvable. In our previous research, we hinted at the feasibility of leveraging additional DLLs (beyond kernelbase) to locate gadgets or construct suitable frames. The only reason we initially relied on kernelbase was due to its convenient and consistent availability of the required primitives. However, this observation may have inadvertently led to a flawed generalization: that DLLs must be used to construct the call stack. But why stop there? Why not leverage the main image base of the target process being injected into or sideloaded?

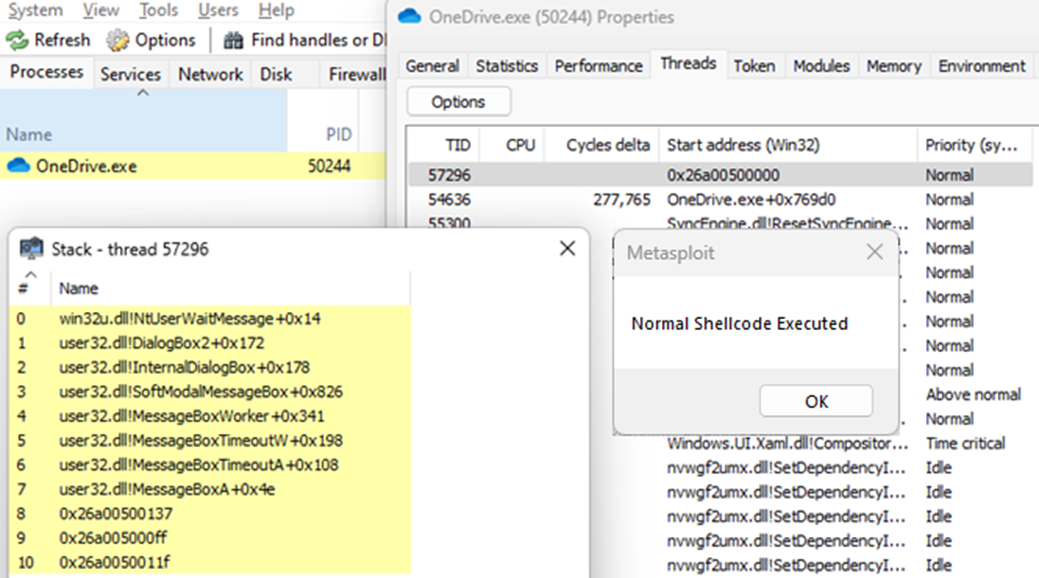

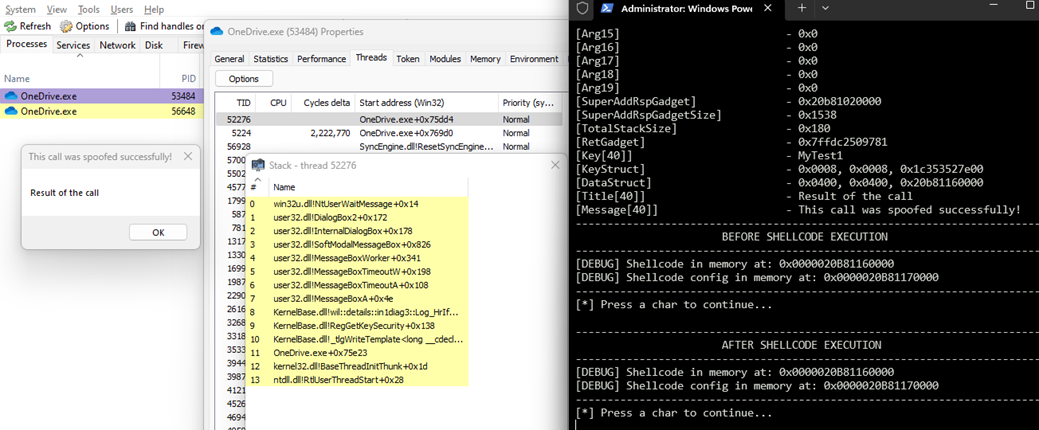

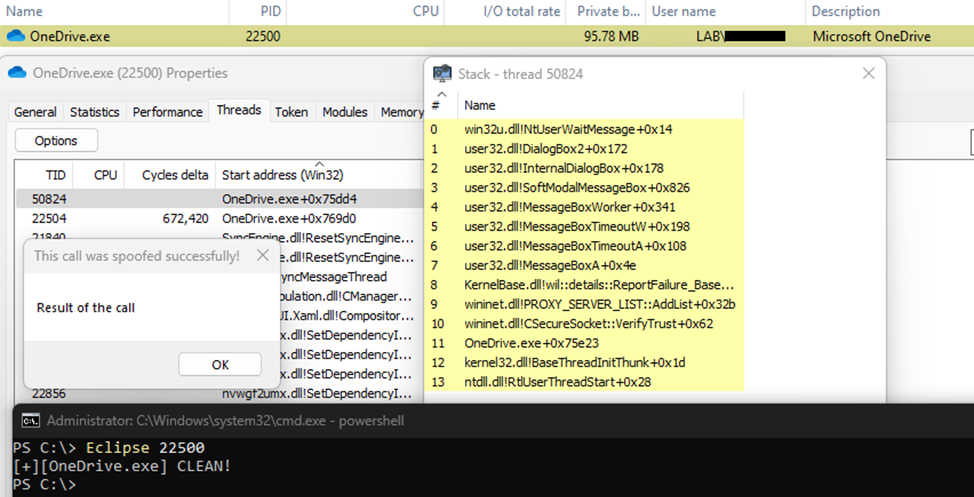

To test this hypothesis, we modified the spoofing routine to allow it to be injected as shellcode and invoked remotely. For comparison, we crafted a standard Metasploit message box shellcode to contrast the indicators shown by a typical in-memory shellcode against one enhanced with stack spoofing. This setup allowed us to observe the practical implications of our approach in a controlled execution environment.

As the target for injection, we selected OneDrive.exe. The rationale for this choice will be discussed in detail in a subsequent section.

For the load-and-execute method, since our focus is not on detection based on injection patterns, we opted for a standard vanilla injection approach using VirtualAllocEx, WriteProcessMemory, and CreateRemoteThread. For the time being, we concentrate solely on analyzing the call stack when a typical MessageBox shellcode is executed in memory.

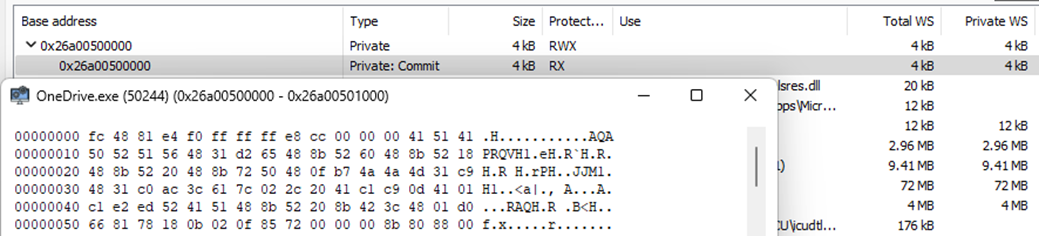

As observed, the call stack is interrupted mid-way, indicating in-memory execution or execution from code lacking Runtime Exception (UNWIND) metadata. The return address on the stack points to the middle of a heap location within the target process, specifically a RWX (read-write-execute) private memory region. Same happens with the Thread Start address, which point to the start of the same memory region, which is where we started the thread with CreateRemoteThread.

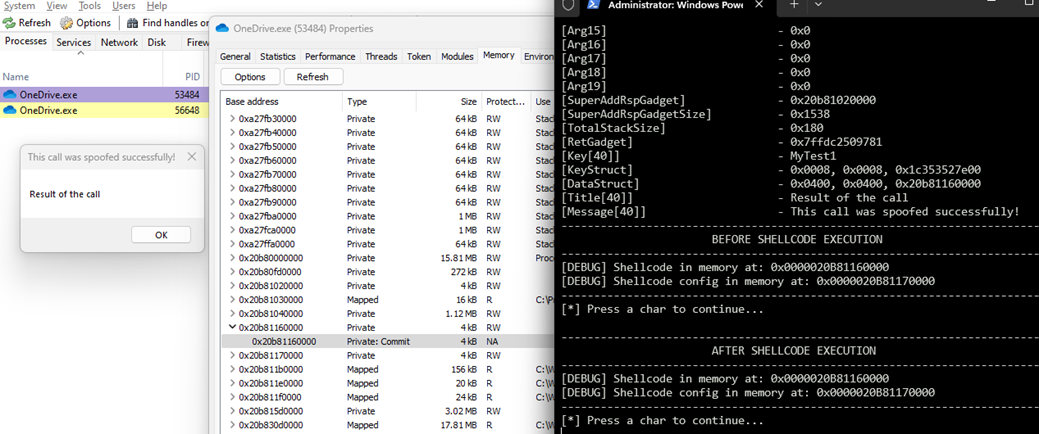

To comprehensively bypass this detection logic, the following conditions must be met:

- Eliminate any direct references to the spoofing caller within the call stack.

- Ensure that the thread’s start address resolves to a legitimate frame (ideally the start of the “final user module”)

- Conceal the presence of RWX or RX memory regions used during execution

As previously discussed, while achieving point (2) is relatively straightforward, it is generally considered infeasible to satisfy conditions (1) and (3) using the stack moonwalk technique. However, our implementation demonstrates otherwise through the following modifications to the original approach:

- The code dynamically resolves the thread start address at runtime, eliminating reliance on compiler intrinsics

- The first stack frame is relocated within the image base of the injected process, ensuring alignment with a legitimate execution context

- A custom ROP chain is established to both encrypt and alter the memory protections of the shellcode region, effectively concealing RWX or RX attributes post-deployment

At this stage, a non-trivial challenge arises: if we push the necessary function pointers onto the stack to decrypt and protect the memory region containing the shellcode, how can we preserve a clean and plausible call stack? The execution of the ROP chain inherently disrupts the expected call-return structure, breaking the stack unwinding mechanisms or, at a minimum, revealing the presence of anomalous or suspicious call sequences.

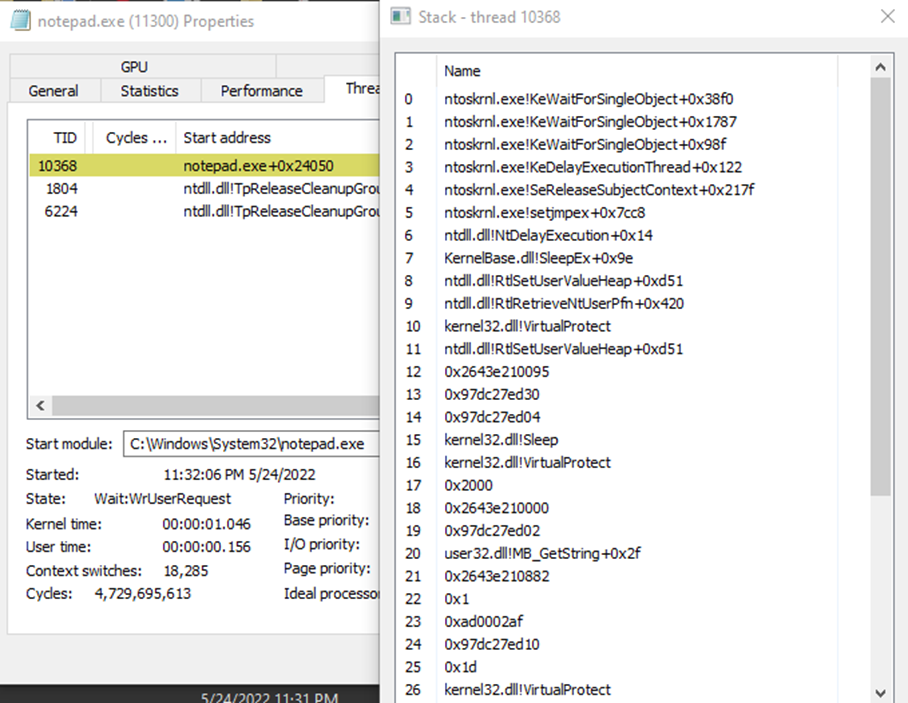

This is precisely what makes techniques based on ROP chains more susceptible to detection. As noted in the research by theFlink (Code White Security) on identifying sleeping beacons DeepSleep, the presence of atypical or fragmented call stacks (often a byproduct of ROP-based execution) serves as a strong heuristic for identifying staged or obfuscated payloads.

Moreover, since the shellcode is now fully encrypted in memory, the stack-restore functionality cannot be reached until the corresponding memory region has been decrypted and its execution permissions restored.

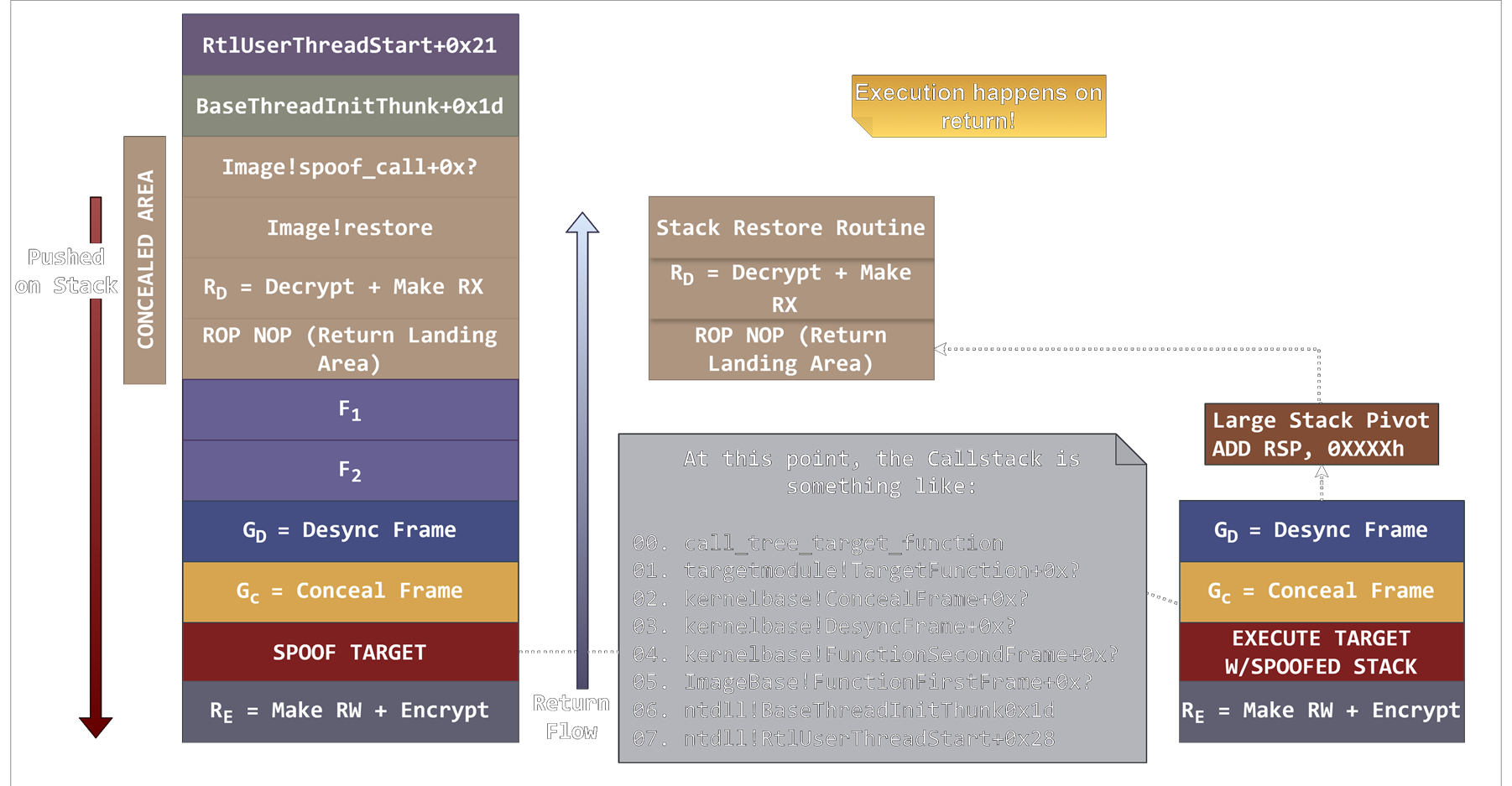

The solution is inherent to a feature offered by the stack moonwalk technique itself. As previously observed, stack moonwalking causes every frame located between the BaseThreadInitThunk frame and the first spoofed frame selected by the technique to become effectively invisible in the reconstructed call stack. This implies that any additional frames inserted within this region, including those used to facilitate decryption or memory protection changes, will also remain hidden from stack-based detection logic.

But how does it help us? Let ( F_1 ), ( F_2 ) be the first two frames selected by the stack moonwalk technique. Let ( G_D ) be the Desync Frame Gadget, and ( G_C ) be the conceal gadget. Let ( R_E ) denote the ROP chain responsible for modifying the memory protection to RW (read-write) and encrypting the shellcode region. Conversely, let ( R_D ) represent the corresponding (specular) ROP chain that performs the inverse operations: decrypting the memory and restoring its protection to RX (read-execute).

The main idea is the following: we will place both ( R_E ) and ( R_D ) chains in the stack. We will place the decryption chain ( R_D ) in the concealed area, while the encryption one ( R_E ) will be pushed after the target function to spoof.

On return, ( R_E ) is executed first, followed immediately by the spoofed function target. At this point, the stack layout conforms precisely to the structure required by the stack moonwalk technique, resulting in a fully unwindable and clean call stack that mimics legitimate execution flow.

Since we cannot rely on the restore function at this stage—due to the shellcode still being encrypted—and we cannot simply continue returning through the stack (as frames ( F_1 ) and ( F_2 ) were never intended to be executed upon return), we need to use a clever, yet simple trick. We will point our desync gadget to a large stack pivot gadget, that will jump over the F frames and land carefully in the conceal area, exactly where we previously place our ( R_D ) chain. This will allow proper decryption of the shellcode in memory. At this point, we can safely redirect execution to the restore function, which will reconstruct the original stack state as it was prior to the spoofing sequence.

Our newly created stack will appear like the following:

The following video shows the technique in action:

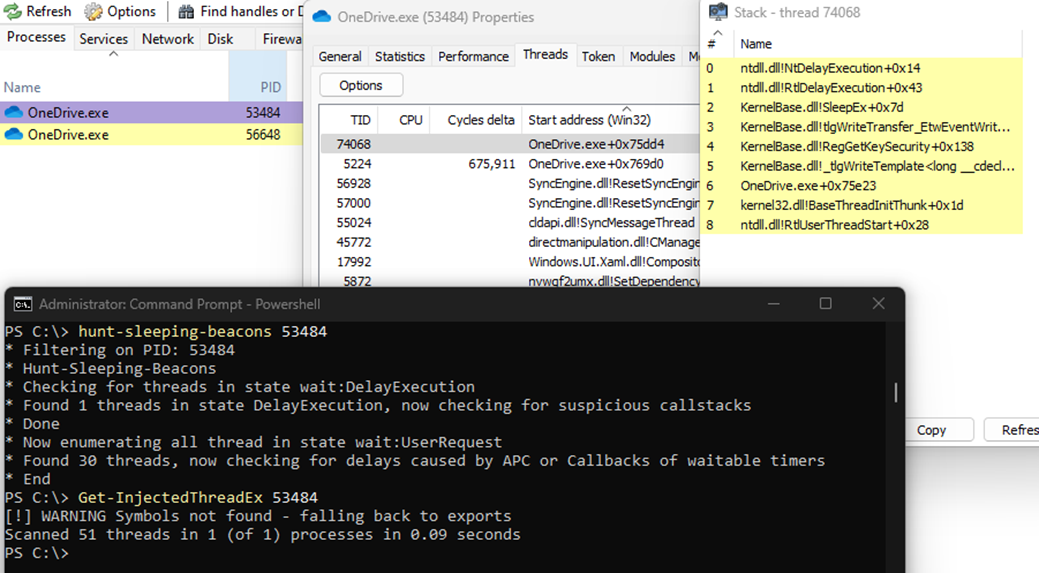

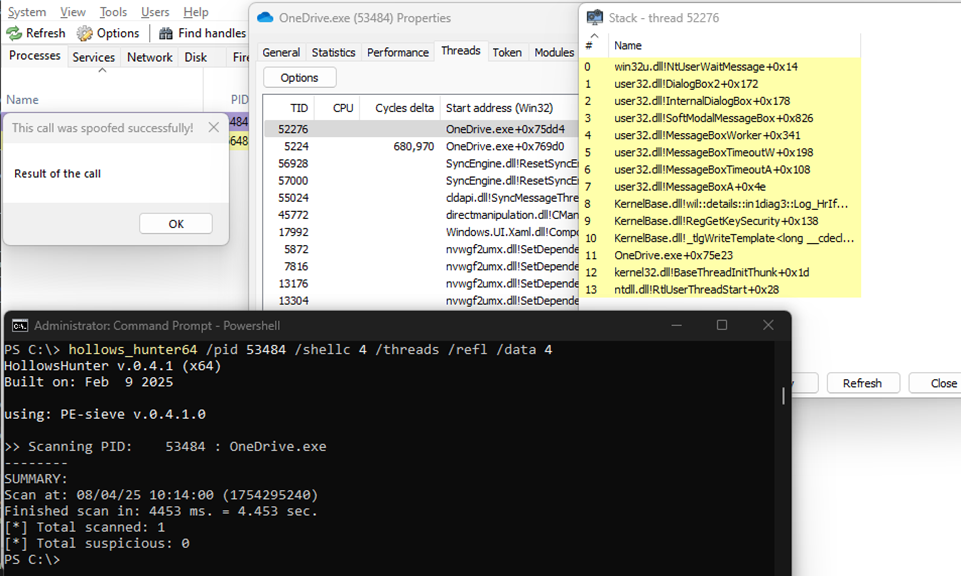

Evasion Evaluation

Public detection tools fail entirely to recognize the call stack tampering introduced by StackMoonwalk++. Notably, tools such as Hunt-Sleeping-Beacons and Get-InjectedThreadEx were unable to identify the SM++ Shellcode or its associated sleeping behavior via call stack analysis.

To ensure a fair evaluation, we explicitly configured the thread to enter a DelayExecution state, a known behavioral signature that these tools are designed to flag. Nonetheless, as demonstrated, both tools failed to detect the presence of our technique.

The excellent hollows_hunter project by hasherazade likewise fails to detect the malicious behavior introduced by StackMoonwalk++, when relying on call stack analysis—as shown in the example below.

However, due to our use of SystemFunction032 as both the encryption and decryption routine, hollows_hunter can detect the encrypted shellcode when running with the /obfus 3 parameter enabled. In this configuration, the tool identifies characteristic patterns of obfuscated memory regions, even though the call stack remains undetectable.

As a final step, we confirmed that the Moonwalk technique, enhanced with the refinements introduced in this blog post, successfully bypasses our publicly available implementation of the Eclipse detection algorithm.

Code

The code for this can be found at Moonwalk++. It is called Moonwalk– thanks to GitHub not allowing + in the name.

Disclaimer

The code is ugly as hell, exactly as the original POC. It should be meant to let you see what is happening without too many complications but… well, I guess you’ll need to figure out some stuff on your own.

Most important files are the ASM ones. The mooninject.asm code, once assembled, is what you will find as shellcode in the POC.

Closing Remarks

Detection often relies on assumptions. Of course, the more fragile those assumptions become, the easier they are to bypass in practice. With that in mind, I wanted to close out the Moonwalk series. This technique has been, in my opinion, seriously underestimated or misunderstood.

On my part, over the past years, I’ve had a lot of fun playing around with it, and this final entry is my way of showcasing how far it could go if pushed a little.

Thanks

As for my previous blogpost on StackMoonwalk, I’d like to thank namazso again for his previous involvement in the research that led to the creation to StackMoonwalk, and for his previous support.

And of course, a huge thanks to my always friends Arash Parsa, aka waldo-irc and Athanasios Tserpelis, aka trickster0, which helped me out with the original Stack Moonwalk research.